Testimonials

Testimonials

The magical universe of Jacques Cloarec (Images — Grimages, theater makeup)

Images Grimages – © Jacques Cloarec

“At a young age, Jacques Cloarec became fascinated with the traditional music and dance of his native Brittany. At twenty, he was president of the Celtic Club at Concarneau. Travelling with his dance troupe to folklore gatherings, he came into contact with various Western traditions: Spanish, Italian, Hungarian, Scottish, Irish, etc.

Initially choosing teaching as his career, when the chance arose he joined the team of the International Institute for Comparative Music Studies of Berlin and Venice, set up to study and disseminate the musical and theatrical expressions of Asia and Africa. As assistant-editor of the UNESCO disc collections, he found the quality of the imagery used for the discs insufficient and taught himself to take photos of musicians and dancers. This led to his interest in theatrical photography, to which he now devoted his time.

He discovered the secrets of oriental make-up, the symbolism of colours in the Kathakali of India and the Kabuki of Japan. His experience of the highly elaborate theatre make-up used in Asian theatre became the very original basis for his general approach to face-masks and make-up, representing the depersonalisation of the actor or dancer, who ceases to be himself and tends to adopt the traits of the god, genie or hero he embodies. Curiously, few women consent to such a depersonalisation, or accept make-up except to accentuate and improve their own traits.

Asian theatre still keeps a tradition that was respected even up to a few centuries ago in the West: all characters are played by boys or men, including all female roles. In Kabuki some actors have specialised in it and are famous for their impersonation of heroines, or princesses, using a make-up that is of prime importance.

In Indian Kathakali, face make-up is classified according to five categories: noble, incisive, bearded, black and ordinary. Noble make-up is suited to gods and heroes. It has a green base. Incisive make-up is used for noble but violent characters: the green is marked with red. Bearded characters are villainous and brutal. The worst have a red beard. White beards are perfidious and refined. The black base indicates uncultivated and barbarous characters. Ordinary make-up is realistic, with a yellow or orange base and is used for women, sages, messangers.

The same conventions are found in China, Japan and Indonesia, as well as Africa, and in ancient Italian comedy. In the West, circus clowns have kept up this tradition. Colour photography is an essential in capturing the symbolism of masks.

Maurice Béjart granted Jacques Cloarec every facility to fix the images of the characters appearing in his ballets. The Italian composer and director Sylvano Bussotti invited him to capture the images of his performances. Jacques Cloarec also followed the great dancer Eric Vu An who, besides his superb technique, embodies the characters he represents with remarkable intensity.

In dressing rooms and backstage, at rehearsals and performances, from the Paris Opéra to Milan’s la Scala, from Lausanne to Palermo, from Brussels to Venice, Jacques Cloarec has pursued actors at every step of their transformation from ordinary humans to the marvellous beings they evoke on stage.”

Alain Daniélou, July 30, 1988

Introduction by the President of the Salon d’automne

Salon d’Automne exhibition in Paris with Jacques Chirac, Édouard Mac Avoy and Jacques Cloarec, 1988.

“The Salon d’Automne 88 will be marked by an exhibition nationwide in scope: “Art treasures of the Côte d’Azur”, within the framework of the “Cent ans de la côte d’azur”.

The history of this unusual centennary is worth recalling for those who are not informed about it. In 1888, a Sub-Prefect, named Liegard, published a novel with the magical title: “Côte d’Azur”, such a booming title that it dethroned the designation “Riviera”.

A committee was set up by Jacques Médecin, the Mayor of Nice, and, it was through close collaboration with Directors Dominique Charpentier and Michel Colas, that we decided, to make every effort, so that “Les trésors d’art de la Côte d’Azur” [The art treasures of the Côte d’Azur], within the framework of the Salon d’automne, at the Grand Palais, should prove to the wider public, even those familiar with its beaches, that sun, sea and its warm sand are not its only riches, and that masterpieces abound there, with the same prodigality.

Here we played our revelatory role: we visited museums, famous foundations and collections, in a quest for exceptional works, from the XVII century up to the most avant-garde manifestations of today, passing through the Belle Époque and the Festival de Cannes.

We can at least say is that our visitors, however violent the contrasts, will see one surprise after another!

I warmly thank all those, Curators of excellent Museums, Mayors and lenders, for their generous participation. Thanks to all of them for having made it possible to gather together so many precious works for the enjoyment of Parisians. Thanks to Jeanne Michèle Hugues for coordinating such an immense task.

We do not forget, nonetheless, that the Salon d’Automne is an attraction, that its sculptors, engravers, painters, architects, weavers and decorators zealously compete, that famous artists who are its faithful contributors welcome an increasing number of young people who, together with their talent, bring us their hope.

Compliments will be paid to the great Loutreuil, and to our friend Jouenne, our active general curator this year; to Abel Gerbaud, to Brabo, to Hans Zeiler, to Mandeville, and to the ardent Germaine Lacaze. We also honour the fine sculptor Kretz, and, with emotion, we recall the major work in contemporary French architecture of our friend Guillaume Gillet, sadly departed. Lastly, the dedicated photographer Jacques Cloarec will present 50 extraordinary photos with the mysterious title “Images-grimages” [Images-face-painting].

May we remain what we are, may our glorious past approve our present, and may our choices be ratified by the future!”

Edouard Mac Avoy

President of the Salon d’Automne, 1988 – Grand Palais – Paris

Le plus clair de mon temps 1926-1987

“Imagine two great porticoes covered with virginia creeper, magnolias, cedars and cypresses, the hills of Latium and a vast dwelling gilded by the sun… Here lives the sage, at Zagarolo, on the hill of the Labyrinth. Here he stores, in his writings, a long adventure lived at Benares, at Madras, at Pondicherry, and among temples lost all over the Indian jungle, a long adventure, with its perils and vicissitudes, a long conquest of the spirit …

“Imagine two great porticoes covered with virginia creeper, magnolias, cedars and cypresses, the hills of Latium and a vast dwelling gilded by the sun… Here lives the sage, at Zagarolo, on the hill of the Labyrinth. Here he stores, in his writings, a long adventure lived at Benares, at Madras, at Pondicherry, and among temples lost all over the Indian jungle, a long adventure, with its perils and vicissitudes, a long conquest of the spirit …

We arrive with Jean-Pierre at the Labyrinth, and the easel has been prepared by Jacques Cloarec, and the colours are waiting for me on the great table: work calls me. Here, society life is banished. If Maurice Béjart comes to spend a few days, he is a friend, almost a pilgrim. Everyone works. The great house lives an intense and secret life. Beauty is there, everywhere around. One breathes it, contemplates it, it dwells in us. One picks the scented peach from the bough…

The serenity of Alain Daniélou is the sum of an exemplary life. He is often silent, abruptly caustic. Never does he display his immense knowledge, but he has an answer to every profound question. He is bright. Wisdom is joyful. And death is one of the curiosities of his life.”

Memoirs Edouard Mac Avoy, published by Ramsay, Paris, 1988.

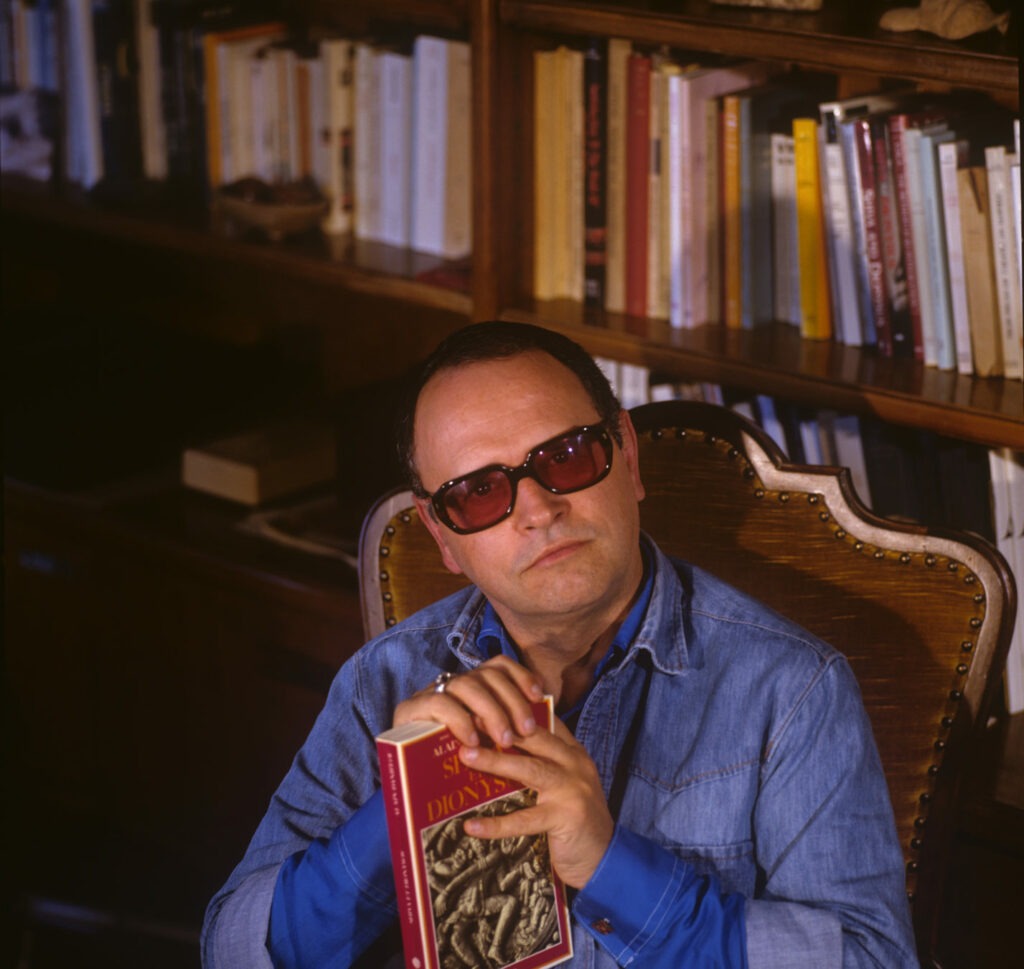

The Journal of Sylvano Bussotti

Sylvano Bussotti – © Jacques Cloarec

“The privilege of friendship and and the guidance of many years of familiarity open secret doors – if we may use an image dear to Cocteau – while keeping obstinately closed illusory accesses, false passages and trompe-l’oeil; guile, the rule in photography, is incompatible with friendship; so, strictly speaking, we would find it difficult to maintain a total and lasting fraternal friendship with a photographer. Sooner or later, having mastered his cameras and aware of his own intentions , his finger will trigger an infinitesimal shot, giving birth to a “monstrous” image that produces a shock. An innocent criminal, the photographer delivers unmoved the most dangerous species in memory, and fixes you in front of the elusive mirror of dark condemnation, caught red-handed, the irrevocable plaything of a consciousness that the celluloid enfolds in the suffocating coils of Adam’s snake. Easy symbols on closer examination, but tangible and actually unchallengeable.

I met Cloarec in 1972 and for fourteen years, the time necessary to reach full puberty, I have been cautiously spying on his movements, happy if I manage to provoke some matchmaking occasions and opportunities, whether on stage or in the shade of flowering trees. I am speaking of the photographer of course – even more rarely does friendship permit the game of surprising or overheard sounds – who, at the time we met, was proud of his ability to make butter, jams and tomato sauce on the country property where he was living, never failing to make sarcastic remarks about artists. What’s more, I fully share the artist’s condition, suffered rather than embraced, eternally calling to mind an incalculable number of issues. But the road from butter to photography took place in part under my own eyes, without a fight, at least in appearance (probably Cloarec’s butter is still exquisite and the first click of his callow fingers on the classical box-camera produced an original image) vindicating the poor artists and turning the eye of our photographer into a form of conscious art.

In the theatre, he always moves with the air of one who knows the way out of the fatal labyrinth. From the point of view of friendship, this may once again appear as a pun alluding to the fact that the hill where his house is located is actually called il Labirinto; to a photograhic awareness, on the other hand, such a fact appears normal. Wings, backdrops and parapets or trick constructions, crossed by winged models in the most outrageous costumes, trace a path that goes straight to photography with deviations: fiction is real, the game won, the pitfalls overcome. The image comes out with a perfection paradoxically – for the theatre – natural of a graceful phantasm. Clouds descend to become incarnate and precious feathers fly directly from the flesh of a male dancer in a sumptuous living canvas that is an unrepeatable performance. Almost as though muddled melodramas were staged on purpose to allow Cloarec’s lenses to accomplish the rite, we find in his shots emotional documents, ready to swear that they know nothing about it.

To say, finally, that the main secret probably dwells in the idea of “giving body”, is not wholly beside the point. Indeed, we admire some of the bodies on the brilliant enamel of some of the photos and an analysis of these bodies shows that they are artistic even before a photographic concept is ready to illustrate them. But it is rare for an artist to feel an acceptance of the body itself as the ancestral model of all the arts. What was lacking was the lens of photography – painting become an exact science – and the mule-headed patience of a countryman. I’m joking. Still prevailing on the brink of the millennium is the growing feeling – a wild plant – of the fecund appearance of humans, whether dressed up in the theatre or undressed and tied to the stake of a woodland pyre. Cloarec is this feeling which he possesses, with a fingering long studied on improbable keyboards, capable of striking images so musical that they unveil, of the fine arts, rites that are separate and taboo. I see it when I look at it and I see and look at what the friend has seen.”

Page 76 of the Journal of Sylvano Bussotti in Zagarolo, april 24, 1986.